Benchmarking

The default Substrate block production systems produce blocks at consistent intervals. This is the known as the target block time. Given this requirement, Substrate based blockchains are only be able to execute a limited number of extrinsics per block. The time it takes to execute an extrinsic may vary based on the computational complexity, storage complexity, hardware used, and many other factors. We use generic measurement called weight to represent how many extrinsics can fit into one block.

In Substrate, 10^12 weight units = 1 second, or 1,000 weight units = 1 nanosecond. This is measured on specific reference hardware: Intel Core i7-7700K CPU with 64GB of RAM and an NVMe SSD.

Substrate does not use a mechanism similar to "gas metering" for extrinsic measurement due to the large overhead such a process would introduce. Instead, Substrate expects benchmarking to provide an approximate maximum for the worst case scenario of executing an extrinsic. Users are charged assuming this worst case scenario path was taken, and if the extrinsic turns out needing less resources, some of the estimated weight and fees can be returned. This is further explained in the Transaction Weights and Fees chapter.

Why benchmark a pallet

Denial-of-service (DoS) is a common attack vector for distributed systems, including blockchain networks. A simple example of such an attack would be for a user to repeatedly execute an extrinsic that involve intensive computation. To prevent users from spamming the network, we charge fee to the user for making that call. The cost of the call should reflect the computation and storage cost incurred to the system such that the more complex the call, the higher the fee. However, we still want to encourage users to use our blockchain system, so we also want this estimated cost to be relatively accurate so we don't charge users more than necessary.

Benchmarking allows developers to charge appropriate transaction fees to end users, corresponding to a more accurate representation of the cost an extrinsic has on the system. Setting a proper weight function that accurately reflects the underlying computation and storage is also an important security safeguard in Substrate.

How to benchmark

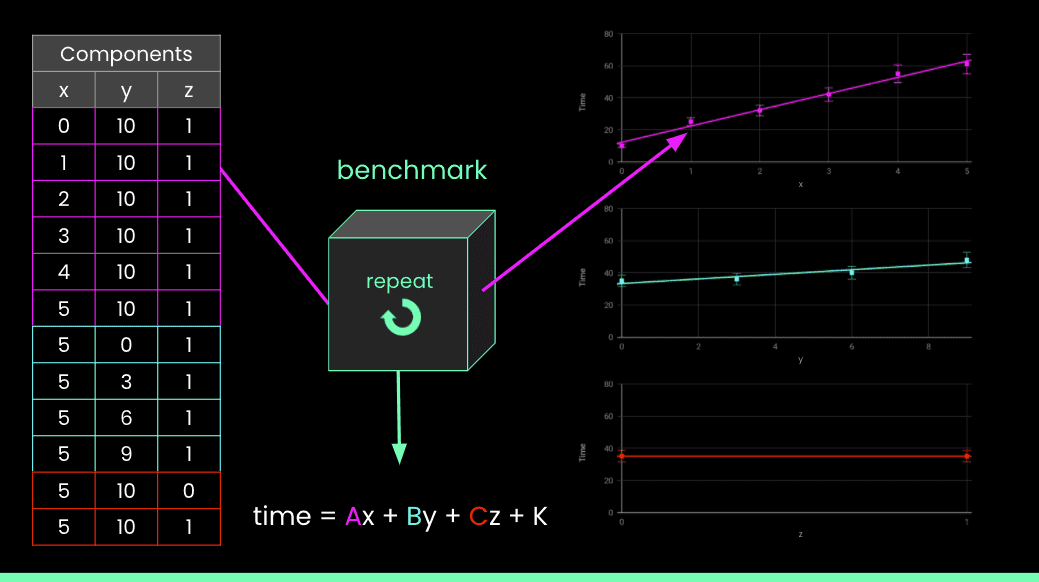

The FRAME benchmarking module has a set of tools to help determine the worst case scenario computation time of runtime extrinsics in order to determine appropriate weights for those extrinsics. It does this by executing a pallet's extrinsics multiple times within a mock runtime environment, and keeps track of the execution time.

In summary, it:

Sets up and executes extrinsics from your pallets.

Captures the raw data of these benchmarks over with these varying inputs, including how many database reads and writes have been performed.

Uses linear regression analysis to determine the relationship between computation time and the extrinsic input.

Outputs a Rust file with ready to use weight functions that can be easily integrated in your runtime.

This framework uses Rust macros to help developers easily integrate bencharking into their runtimes. A Substrate benchmark will look something like this:

benchmarks! {

benchmark_name {

/* set-up initial state */

}: {

/* the code to be benchmarked */

} verify {

/* verifying final state */

}

}

You can see that the benchmark macro:

- Sets up the initial state before running the benchmark.

- Measures the execution time, along with the number of database reads and writes.

- Verifies the final state of the runtime, ensuring that the benchmark executed as expected.

You can configure your benchmark to run over different varying inputs. For each input, you can configure the range of those variables, and use them within the benchmark set-up or execution logic.

The full syntax and functionality can be seen in the benchmarks! macro API

documentation.

Best practices and common patterns

There are a few best practices for writing extrinsics in order to avoid any surprise on your extrinsics computation time and benchmarking.

Initial weight calculation must be lightweight

Extrinsic weight function will be called, probably multiple times, when an extrinsic is going to be called. So the weight function must be lightweight and should not perform any storage read/write, an expensive operation.

Set bounds and assume worst case

If the extrinsic computation time depends on an existing storage value, then set a maximum bound on those storage items and assume the worst case. Once the actual weight is known, the difference can be returned in the extrinsic.

Keep extrinsics simple

Try to keep an extrinsic simple and to perform only one function. Sometimes it may be better to separate the complex logic into multiple extrinsic calls and have a front-end abstracting these extrinsic interactions away to provide a clean and friendly user experience.

Separate benchmarks per logical path and use the worst case

If your extrinsic has multiple logical paths with signficantly different execution time, separate

these paths in multiple benchmarking cases and measure them. In the actual pallet weight macro above

the extrinsics, you could combine them with a max function, e.g.

#[pallet::weight(

<T::WeightInfo::path_a()

.max(T::WeightInfo::path_b())

.max(T::WeightInfo::path_c())>

)]

Note the weight returned here is more as the worst case of the weight estimate. You can then decide if you want to return some weight value back at the end of the extrinsic once you know what computations have happened. Otherwise it will be always overcharging users for calling this extrinsic.

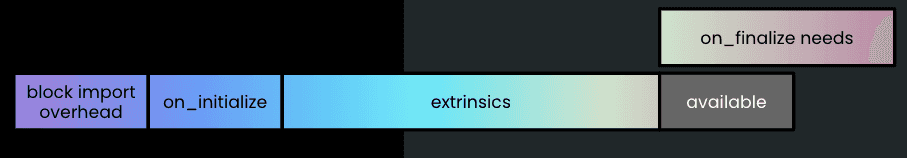

Minimize usage of on_finalize, and transition logic to on_initialize

Substrate provides runtime developers with multiple hooks when writing their own runtime, with

on_initialize and on_finalize being two of them. As on_finalize is the last thing that happens in

a block, variable weight requirements in on_finalize can easily lead to an overweight block and should be

avoided.

If possible, move the logic to on_intialize hook that happens at the beginning of the block. Then

the number of extrinsics to be included in the block can be adjusted accordingly. Another trick is

to put the weight of on_finalize on to on_initialize or the extrinsic itself. This leads to

another tip of trying to keep the pallet hook execution in constant time for only set up and clean

up, but not doing fancy computation.

Command arguments

To find out what the different CLI commands do, run:

cargo build --features runtime-benchmarks --help

Here's an example of launching a node with benchmarking features enabled:

./target/release/node-template benchmark \

--chain dev \ # Configurable Chain Spec

--execution wasm \ # Always test with Wasm

--wasm-execution compiled \ # Always used `wasm-time`

--pallet pallet_example \ # Select the pallet

--extrinsic '\*' \ # Select the benchmark case name, using '*' for all

--steps 20 \ # Number of steps across component ranges

--repeat 10 \ # Number of times we repeat a benchmark

--raw \ # Optionally output raw benchmark data to stdout

--output ./ # Output results into a Rust file

A recent argument that has been introduced is --template. With it, you can specify your own weight

template file and the benchmarking toolchain will fill in the exact numbers from the measured

result. This enables automating weight generation in your desired code format and integrates this

in your CI process.

The template is in rust handlebars format.

Example

Let's take accumulate_dummy benchmark case from the example pallet

as an example.

accumulate_dummy {

let b in 1 .. 1000;

let caller = account("caller", 0, 0);

}: _ (RawOrigin::Signed(caller), b.into())

Using the benchmarking CLI, we can specify the number of steps and repeats. This means how many steps will be taken to walk through each variable range, and how many times the execution state will be repeated.

For example:

./target/release/node-template benchmark \

--chain dev \

--execution wasm \

--wasm-execution compiled \

--pallet pallet_example \

--extrinsic '\*' \

--steps 20 \

--repeat 10 \

--raw \

--output ./pallets/example/weights.rs

With --steps 20 --repeat 10 in the benchmark input arguments, b will walk 20 steps to reach

1,000, so b will start from 1 and increment by about 50. For each value of b, we will execute

the benchmark 10 times and record the benchmark information. The resulting weights will be outputted

into a weights.rs file.

Raw data output

The first output is the raw data recording how much time is spent on running the execution state when varying the input variables. At the end for each variable, the coefficient, assuming linear relationship, between the execution time with respect to change in the variable is determined.

This is a snippet of the output:

Pallet: "pallet_example", Extrinsic: "accumulate_dummy", Lowest values: [], Highest values: [], Steps: [10], Repeat: 5

b,extrinsic_time,storage_root_time,reads,repeat_reads,writes,repeat_writes

1,1231926,162640,1,4,1,2

1,1245146,128021,1,4,1,2

1,1238746,126051,1,4,1,2

1,1206004,126391,1,4,1,2

1,1212564,127941,1,4,1,2

100,1257646,129750,1,4,1,2

100,1232476,125780,1,4,1,2

100,1215466,128310,1,4,1,2

100,1205835,129070,1,4,1,2

...

991,1208294,125820,1,4,1,2

991,1209305,126921,1,4,1,2

991,1203275,125031,1,4,1,2

991,1234855,124190,1,4,1,2

991,1337136,125060,1,4,1,2

Median Slopes Analysis

========

-- Extrinsic Time --

Model:

Time ~= 1231

+ b 0

µs

Reads = 1 + (0 * b)

Writes = 1 + (0 * b)

Min Squares Analysis

========

-- Extrinsic Time --

Data points distribution:

b mean µs sigma µs %

1 1230 12.61 1.0%

100 1230 16.53 1.3%

199 1227 12.88 1.0%

298 1215 12.94 1.0%

397 1239 19.83 1.6%

496 1234 18.51 1.5%

595 1228 7.167 0.5%

694 1233 13.51 1.0%

793 1218 9.876 0.8%

892 1225 14.15 1.1%

991 1220 11.63 0.9%

Quality and confidence:

param error

b 0.006

Model:

Time ~= 1230

+ b 0

µs

Reads = 1 + (0 * b)

Writes = 1 + (0 * b)

With the median slopes analysis, this is the weight function:

1231 µs + (0 * b) +

[1 + (0 * b)] * db read time +

[1 + (0 * b)] * db write time

We separate the db/storage read and write out because they are particularly expensive and their

respective operation time will be retrieved from the runtime. We just need to measure how many db

read write are performed with respect to the change of b.

The benchmark result is telling us that it will always perform 1 db read and 1 db write no matter

how b changes.

The benchmark library gives us both a median slope analysis; that the execution time of a particular

b value is taken as the median value of the repeated runs, and a min. square

analysis that is better explained in a statistics

primer.

You can also derive your own coefficients given you have the raw data on each run, say maybe you know the computation time will not be a linear but an O(nlogn) relationship with the input variable. So you need to determine the coefficient differently.

Auto-generated WeightInfo implementation

The second output is an auto-generated WeightInfo implementation. This file defines weight

functions of benchmarked extrinsics with the computed coefficient above. We can directly integrated

this file in your pallet or further customize them if so desired. The auto-generated implementation

is designed to make end-to-end weight updates easy.

To use this file, we define a WeightInfo trait, for example in the Example pallet:

pub trait WeightInfo {

fn accumulate_dummy(b: u32, ) -> Weight;

fn set_dummy(b: u32, ) -> Weight;

fn sort_vector(x: u32, ) -> Weight;

}